Egon Schiele’s exhibit at the Neue Galerie defines incompletion. Most of his paintings, drawings and watercolors are portraits missing an arm or lacking a torso; most are sparsely colored. In particular, his male studies (including of himself) are emaciated shadows of real men. Is it fitting that Schiele’s life, too, was interrupted. He died of influenza at the age of 28.

It isn’t that Schiele’s works aren’t fully realized. They are. He trained at the

Schiele never had to search for subjects. In art school, he drew the people of

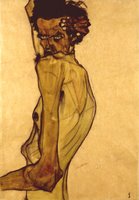

Schiele’s focus on the human form gets draped in black in his staggering portrait of Max Oppenheimer. The svelte painter’s gaze is haunting, as are his fingers that hang from his arm like a wet mop. Though Schiele’s lines of ink and black crayon are sparse – as are his watercolors and gouaches – they’re full of weight. Schiele’s Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted Above Head is true to style. His naked body is starved. His bones and eyes poke out from under his skin.

Schiele was one-of-a-kind, and remains a distinctive voice from the past. Like his themes of emptiness, starkness and wasting, today’s world of art is less full for his early death.

1 comment:

nicely edited

Post a Comment